A prototype JP2 validator and properties extractor

A few months ago I wrote a blog post on a simple JP2 file structure checker. This led to some interesting online discussions on JP2 validation. Some people asked me about the feasibility of expanding the tool to a full-fledged JP2 validator. Despite some initial reservations, I eventually decided to dedicate a couple of weeks to writing a rough prototype. The first results of this work are now ready in the form of the jpylyzer tool. Although I initially intended to limit its functionality to validation (i.e. verification against the format specifications), I quickly realised that since validation would require the tool to extract and verify all header properties anyway, it would make little sense not to include this information in its output. As a result, jpylyzer is both a validator and a properties extractor.

Validation in a nutshell

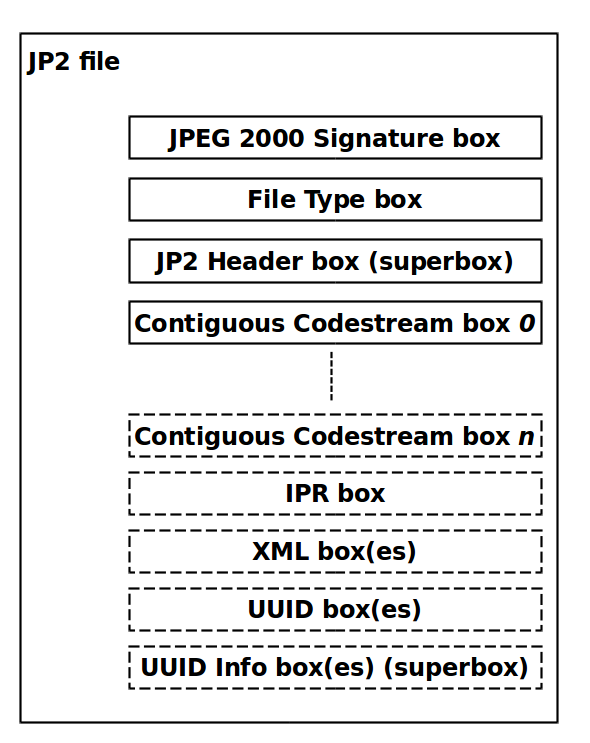

It is beyond the scope of this blog post to provide an in-depth description of how jpylyzer validates a JP2 file. This will all be covered in detail by a comprehensive user manual, which I will try to write over the following weeks. For now I will restrict myself to a very brief overview. First of all, it is helpful here to know that internally a JP2 file is made up of a number of building blocks that are called ‘boxes’. This is illustrated by the figure below:

Some of these boxes are required (indicated by solid lines in the figure), whereas others (depicted with dashed lines) are optional. Some boxes are ‘superboxes’ that contain other boxes. A number of boxes can have multiple instances, whereas others are always unique. In addition, the order in which the boxes may appear in a JP2 file is subject to certain restrictions. This is all defined by the standard. At the highest level, jpylyzer parses the box structure of a file and checks whether it follows the standard. At a lower level, the information that is contained within the boxes is often subject to restrictions as well. For instance, the header field that defines how the colour space of an image is specified only has two legal values; any other value is meaningless and would therefore invalidate the file. Finally, there are a number of interdependencies between property values. For instance, if the value of the ‘Bits Per Component’ field of an image equals 255, this implies that the JP2 Header box contains a ‘Bits Per Component’ box. There are numerous other examples; the important thing here is that I have tried to make jpylyzer as exhaustive as possible in this regard.

It is also worth pointing out that jpylyzer checks whether any embedded ICC profiles are actually allowed, as JP2 has a number of restrictions in this regard. There is a slight (intentional) deviation from the standard here, as an amendment to the standard is currently in preparation that will allow the use of “display device” profiles in JP2. The current version of jpylyzer is already anticipating this change, and will consider JP2s that contain such ICC profiles valid (provided that they do not contain any other errors of course).

What’s not included yet

As this is a first prototype, jpylyzer is still a work in progress. Although most aspects of the JP2 file format are covered, a few things are still missing at this stage:

- Support of the Palette and Component Mapping boxes (which are optional sub-boxes in the JP2 Header Box) is not included yet. The current version of jpylyzer recognises these boxes, but doesn’t perform any analyses on them. This will change in upcoming versions.

- The IPR, XML, UUID and UUID Info boxes are not yet supported either.

- The analysis and validation of the image codestream is still somewhat limited. Currently jpylyzer reads and validates the required parts of the main codestream header (for those who are in the know on this: the SIZ, COD and QCD markers). It also checks if the information in the codestream header is consistent with the JP2 image header (the information in both headers is partially redundant). Finally, it loops through all tile parts in an image, and checks if the length (in bytes) of each tile-part is consistent with the markers that delineate the start and end of each tile-part in the codestream. This is particularly useful for detecting certain types of image corruption where one or more bytes are missing from the codestream (either at the end or in the middle).

- For now only codestream comments that consist solely of ASCII characters are reported. As the standard permits the use of non-ASCII characters of the Latin (ISO/IEC 8859-15) character set, this means that codestream comments that contain e.g. accent characters are currently not reported by jpylyzer. This will change in upcoming versions.

Downloads

You can download the source code of jpylyzer from the following location1:

https://github.com/bitsgalore/jpylyzer/

This requires Python 2.7, or Python 3.2 or more recent. A word of warning though: due to a number of reasons the source code ended up somewhat clumsy and unnecessarily verbose (one colleague even remarked that looking at it induced nostalgic memories of good old GW-BASIC!). With some major refactoring the overall length of the code could probably be reduced to half its current size, and I may have a go at this at some later point. For now it’ll have to do as it is!

I also created some Windows binaries for those who do not want to install Python. Just follow the link below, download the ZIP file and extract it to an empty directory. Then simply use ‘jpylyzer.exe’ directly on the command line:

https://github.com/bitsgalore/jpylyzer/downloads

A final word

Keep in mind that the current version of jpylyzer is still a prototype. There may (and probably will) be unresolved bugs, and it really shouldn’t be used in any operational workflows at this stage. So far I have tested it with a range of JPEG 2000 images (mostly JP2, but also some JPX), including some images that I deliberately corrupted. No matter how corrupt an image is, this should never cause jpylyzer to crash. Therefore, it would be extremely useful if people could test the tool on their worst and weirdest images, and report back in case of any unexpected results. For early 2012 I’m also planning to write a comprehensive user guide that gives some more details on the validation process, as well as an explanation on the reported properties. Support of the JP2 boxes that are currently missing will also follow around that time. Meanwhile, any feedback on the current prototype is highly appreciated!

Originally published at the Open Preservation Foundation blog

-

Postscript, February 2019 - all links in this section point to an insanely outdated version of jpylyzer! Don’t use them, but go to the jpylyzer web site at http://jpylyzer.openpreservation.org/ instead (unless you’re some future software historian with an unlikely interest in the history of jpylyzer). ↩

-

JP2

- Generating lossy access JP2s from lossless preservation masters

- Jpylyzer 2015 round-up

- Response to report on JPEG 2000 expert round table

- Six ways to decode a lossy JP2

- Jpylyzer software finalist voor digitale duurzaamheidsprijs

- Optimising archival JP2s for the derivation of access copies

- ICC profiles and resolution in JP2: update on 2011 D-Lib paper

- Automated assessment of JP2 against a technical profile

- Update on jpylyzer

- Jpylyzer documentation

- A prototype JP2 validator and properties extractor

- A simple JP2 file structure checker

- Paper on JPEG 2000 for preservation

- Ensuring the suitability of JPEG 2000 for preservation

-

jpeg-2000

- Generating lossy access JP2s from lossless preservation masters

- Jpylyzer 2015 round-up

- Response to report on JPEG 2000 expert round table

- Six ways to decode a lossy JP2

- Jpylyzer software finalist voor digitale duurzaamheidsprijs

- Optimising archival JP2s for the derivation of access copies

- ICC profiles and resolution in JP2: update on 2011 D-Lib paper

- Automated assessment of JP2 against a technical profile

- Update on jpylyzer

- Jpylyzer documentation

- A prototype JP2 validator and properties extractor

- A simple JP2 file structure checker

- Paper on JPEG 2000 for preservation

- Ensuring the suitability of JPEG 2000 for preservation

-

jpylyzer

- Generating lossy access JP2s from lossless preservation masters

- Jpylyzer 2015 round-up

- Jpylyzer software finalist voor digitale duurzaamheidsprijs

- Adventures in Debian packaging

- Automated assessment of JP2 against a technical profile

- Update on jpylyzer

- Jpylyzer documentation

- A prototype JP2 validator and properties extractor

- A simple JP2 file structure checker

Comments